The Dôle is a Valais AOC -certified red wine made from pure Pinot Noir, which was harvested, weighed, probed and vinified in the Swiss canton of Valais, or from a mixture of red grape varieties also permitted and cultivated in Valais, this mixture must consist of at least 85% Pinot noir and Gamay grape varieties . The Pinot Noir must predominate in this 85%. Any addition is forbidden. The Pinot noir and the Gamay are traditional red grape varieties in Valais, to which the designation Grand Cru is reserved. All grape varieties of the Dôle Grand Cru must meet the requirements of the Valais red wines of the Grand Cru category.

Origin and name customer

In 1820 the Geneva botanist and natural scientist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle named the red wine grape variety Gamay from the French city of Dole with the name “Dôle”. The first vines in this regard came to Valais in 1850. The name “Dôle”, originally associated with the Gamay grape variety, later referred to Pinot noir, before the name finally referred to a Valais mixture of both types. Pinot noir from Burgundy was also introduced in Valais by the Council of State in the middle of the 19th century.

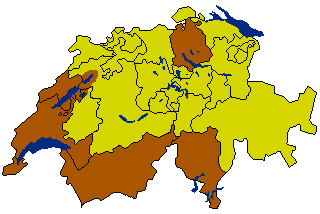

The name “Dôle” has been protected since 1959. This means that from this year on, the name “Dôle” will only be used for related wines that explicitly come from the canton of Valais.

Walliser Pinot Noir

The Valais Act requires the Dole or Pinot noir appellation d’origine contrôlée or AOC du Valais a minimum Oechsle degree of 83 ° Oe and current boundaries per unit area of 1.2 kg per m 2 , or 0.96 l per m 2 (must), for the Dôle or Pinot noir Grand Cru or GC du Valais of 91.9 ° Oe and 0.8 kg per m 2 or 0.64 l per m 2 (must).

Walliser Cuvée

The Dôle is the most famous red wine -Cuvée (red Cuvée or assemblage wine) from Switzerland. It consists of at least 85% Pinot noir and Gamay, and a maximum of 15% other varieties such as Syrah, Humagne and Cornalin, all of which must also be approved in Valais. Syrah and Humagne rouge are also traditional red grape varieties in Valais, and Cornalin is an indigenous red grape variety that is also designated as Grand Cru. The proportion of Pinot Noir must be at least 51%. The minimum must weight is 83 degrees Oechsle required. For the classification as Dôle, maximum yield limits apply for the individual varieties, which are set by the canton.

The Pinot noir gives the Valais Cuvée its strong structure, while the Gamay gives it intense aromatic components as well as a fresh and supple character.

Valais rosé

The Weisse Dôle (French La Dôle blanche ) is a white Valais AOC – Rosé made from the same grape varieties as the Dôle, which is considered a summer wine. It can also be blended up to 10% with Valais AOC white wines. The red grapes are pressed without their skin. Very pale in color, it has a fruity and full-bodied character with a slightly sweet finish. It goes well with an aperitif and tapas as well as upscale dishes (also spicy) and Asian cuisine.

Valais country wine

If the required minimum must weight is not reached, the Dôle can be marketed under the name Goron , whereby these grapes were also harvested, weighed, probed and vinified exclusively in Valais. The name “Goron” has been protected since 1998. The Goron is primarily consumed locally in Switzerland itself. The white pressed Rosé de Goron also comes exclusively from grapes that have been harvested, weighed, probed and vinified in Valais. These are Valais country winesThe traditional names “Goron” and “Rosé de Goron” are not accompanied by a geographical reference. If the wine in question comes solely from the Pinot noir or Gamay grape variety, it can also be used as a grape variety name combined with a geographical designation such as Swiss Pinot noir , Swiss Gamay , Swiss Rosé de Pinot noir , Swiss Rosé de Gamay etc. and the note “Landwein” (“LW”, Frech Vin de pays ) are brought into the trade.

The red Valais country wine Goron should not be confused with the Valais grape variety Goron Bovenier.

Source: Wiki